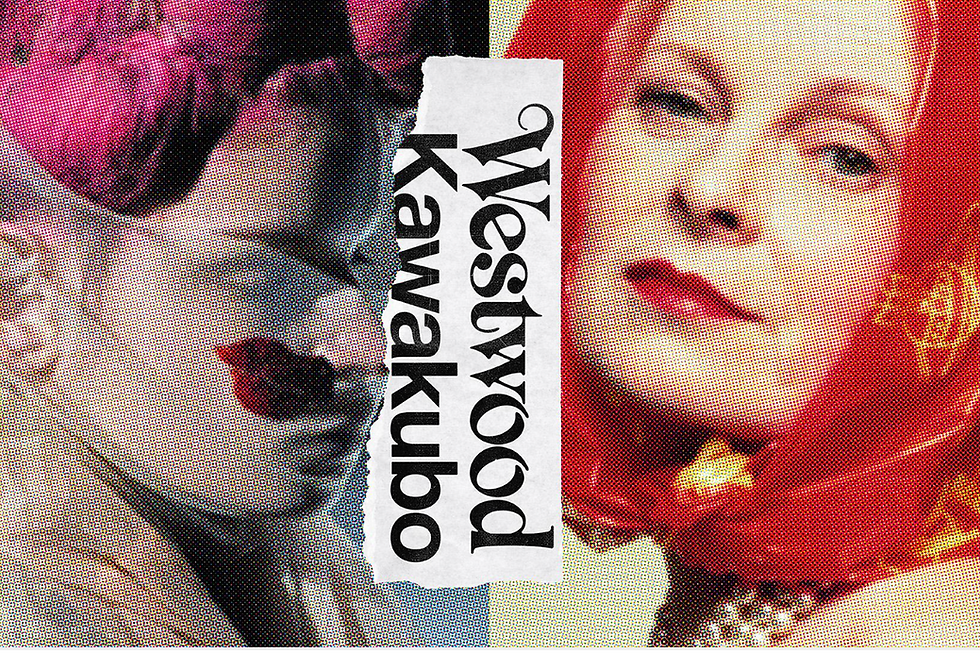

Westwood | Kawakubo: When Punk Met the Avant-Garde (and Both Refused to Behave).

- Sep 19, 2025

- 3 min read

The NGV has gone and done it again. Come December 2025, Melbourne will play host to a sartorial showdown of two of fashion’s most subversive visionaries: Vivienne Westwood and Rei Kawakubo. It’s a pairing that feels inevitable in hindsight - two women born a year apart, continents away, both autodidacts who gleefully thumbed their noses at tradition and remade fashion in their own anarchic image.

Westwood turned punk into an international contagion - tartan, safety pins, and bondage trousers weaponised into social commentary - while Kawakubo turned absence itself into a presence, slicing and warping silhouettes into philosophical riddles. Westwood declared fashion political; Kawakubo made it metaphysical. And now, for the first time, they’ll speak in tandem through more than 140 radical designs assembled from the world’s most coveted archives.

This is not your polite costume drama. Expect riotous punk relics - the leather, chains and tees that powered the Sex Pistols - colliding with Kawakubo’s sculptural abstractions, from petal-like ensembles to the infamous "lumps and bumps" that redefined the female body in the late '90s. Think Westwood’s 18th-century courtly gowns (as seen on Kate Moss, all undone glamour) strutting alongside Kawakubo’s vinyl and jacquard insurgencies. It’s a pas de deux where one partner is screaming into a megaphone and the other is whispering koans about form, void and beauty.

And it’s more than spectacle. The NGV is staging this as a serious cultural moment - backed by heavyweight lenders like the Met and the V&A, bolstered by recent gifts from Comme des Garçons itself. Context matters: Kawakubo’s works come haloed by her 2017 Met retrospective, while Westwood’s archive carries the weight of her political crusades, from anti-capitalist manifestos to climate protest banners. Both used clothes not as decoration but as declaration.

There’s also the delicious friction: Westwood revelled in parodying the establishment even as she courted it, while Kawakubo has remained defiantly elusive, granting few interviews, allowing the clothes themselves to provoke confusion, awe, or outrage. Westwood’s stage was the street and the runway as theatre; Kawakubo’s stage has always been the idea itself.

What makes this exhibition cheekily irresistible is that NGV has leaned into their differences rather than smoothing them out. Galleries will be staged in dramatic symmetry - as if left and right hands, identical in gesture but not in fingerprint. Expect the tartans and tweeds of London punk tailors to spar with the restrained greys and deconstructed suits of Tokyo minimalism. Expect silk taffeta gowns glinting under spotlights next to pink vinyl experiments that sneer at tradition.

And let’s not ignore the star power. Rihanna’s unforgettable Met Gala petal dress? Check. Sarah Jessica Parker’s corseted Westwood wedding gown from Sex and the City? Check. Pieces worn by Gaga, Katy Perry, Tracee Ellis Ross? All here. It’s a show dripping in pop-cultural wattage while still grounded in intellectual depth.

This is not just an exhibition - it’s a manifesto in fabric. Punk and Provocation, Rupture, Reinvention, The Body, The Power of Clothes: each theme reads like a reminder that Westwood and Kawakubo never designed outfits; they designed arguments.

The NGV has positioned itself as the southern hemisphere’s capital of fashion exhibitions, but Westwood | Kawakubo feels like a flex even by their standards. If previous blockbusters were about spectacle, this one is about putting two voices - loud, insistent, unignorable - into dialogue. Fashion here isn’t the frock on your back, it’s the language of rebellion.

Come December, Melbourne won’t just be hosting a blockbuster - it’ll be staging the ultimate clash of style philosophies: Sex Pistols vs. Zen puzzles, corsets vs. voids, tartan vs. abstraction. And in true Westwood and Kawakubo spirit, there will be no neat resolutions. Only provocation.

---

Words by AW.

Photo courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria.